As beer makers, we worry a lot about when to brew. We worry about temperature. We worry about timing. We worry about whether the lunch we put in the staff fridge has been stolen for a third day in a row (I’m looking at you, Bradford…)

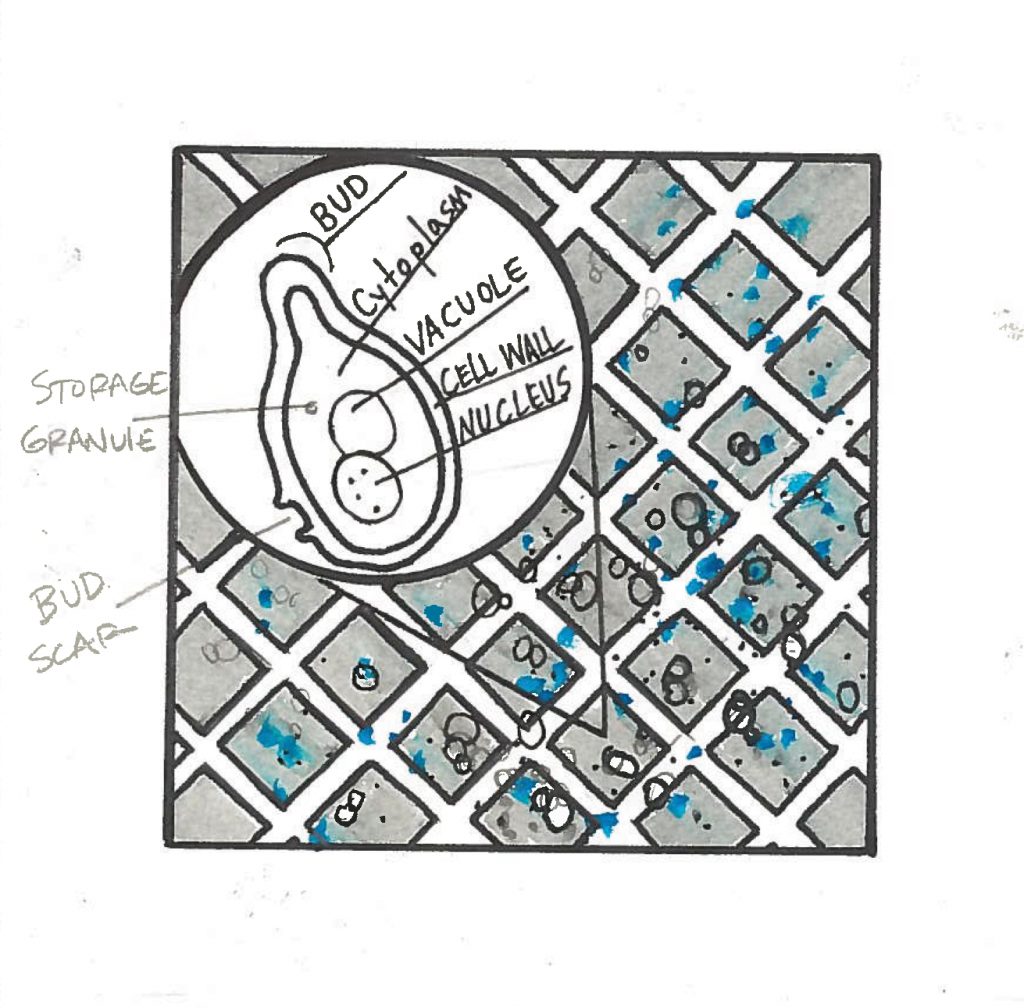

But one of the details we worry about that doesn’t get much buzz is a little known quality called flocculation. What is flocculation? Well, since 65% of you are visual learners, let’s whip out the drawings.

This is a yeast cell. That happy little guy is what consumes the sugars in our beer and spits them out as alcohol and carbon dioxide. A lot of people think that when a yeast cell is all out of sugar, it will die. But our little yeast is no weakling. See next visual, learner.

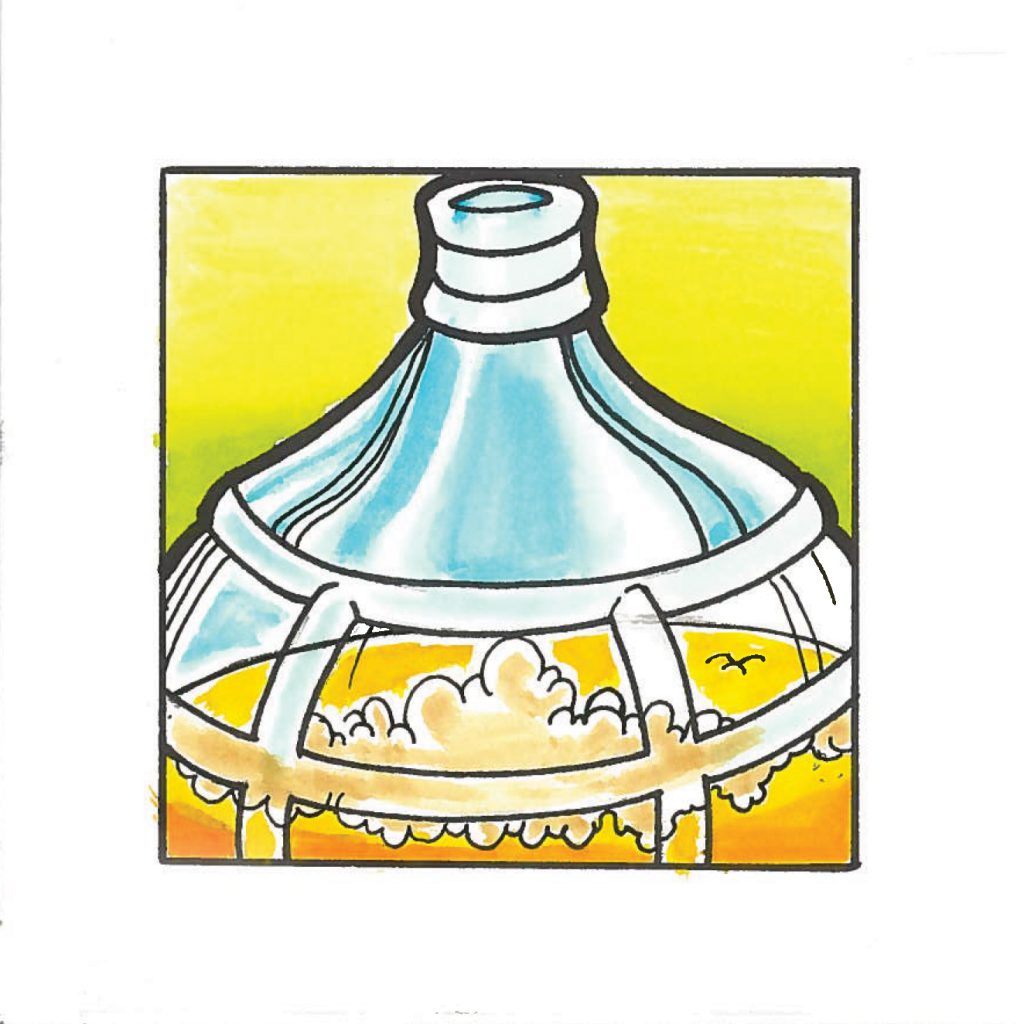

You see, when yeast are done working, they take a break and go dormant. If we were to add more sugar for them to eat, or put that yeast into a new batch of beer, then they’d start back up again and go back to work as usual. Before they do that though, they must flocculate!

Flocculating is when yeasts come together in big clumps. It’s a sort of survival mechanism, with less nutrients available, bonding together can help them share resources. But different yeasts flocculate in different ways. Ale yeasts will flocculate side by side, forming a sort of raft that’s carried to the top of the tank by bubbles of CO2; this is why we refer to ale yeast as “top-fermenting,” even though the work of fermentation is actually being done all throughout the tank.

Lager yeast, on the other hand, comes together in big balls, and will fall down to the bottom of the tank, which is why it’s called “bottom-fermenting.” Ale yeast will eventually end up down here too, once their rafts all sink. From here, most brewers will open a valve at the bottom of the tank and capture all of that compacted yeast at the bottom to start the next batch of beer. And the circle of flocculation continues.

But not all yeast are so social. In fact, most wild yeasts don’t flocculate at all. We as brewers have coaxed them into being more flocculent (AKA less anti-social) through multiple generations of natural selection, because it makes our lives easier – and our beer brighter – if the yeast all settle together when the fermentation is done.

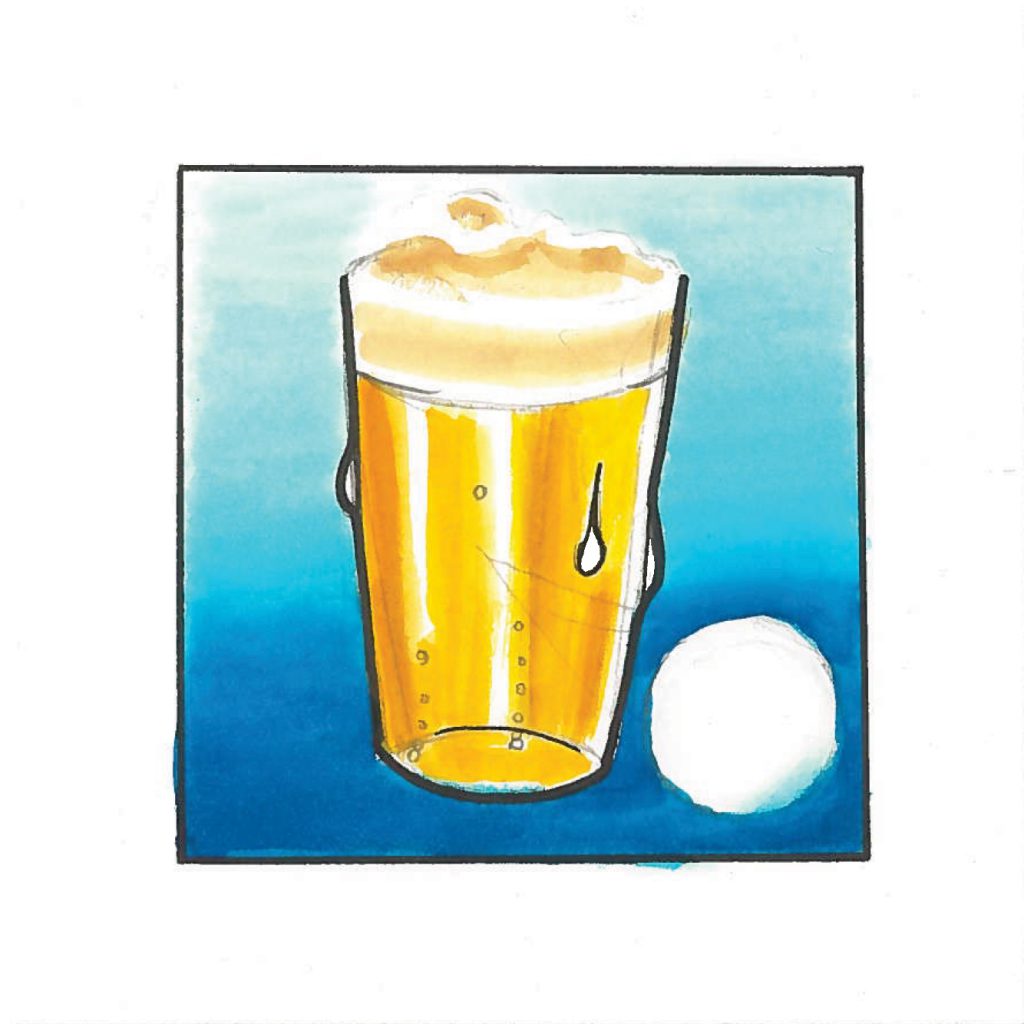

Some yeasts, like those used in Hefeweizens and hazy IPAs, generally are not too pumped on flocculating. The result is a beer with the yeast still in it, which not only makes it cloudy, but also gives it a big yeasty flavor, too. Our Zero Flocs Given IPA is one of those special beers: It looks more like a pint of orange juice than a traditional ale. Without all of those stubborn, non-flocculating yeast, this beer wouldn’t taste quite as good, or be nearly as interesting.

All illustrations by Kadriya Truvillion. Check out her illustrations and tattoo art on Instagram @truvillainy

If you’d like to get your hands on some of our Zero Flocs Given IPA, we’ll be releasing it for the first time ever in 16oz cans at the Public House on October 20th. Because just like this yeast, you should never settle.